Patriotism for the Perpetual Foreigner

Japanese Internment Camp Curriculum and Identity Formation

Kylie Baker

24 November 2014

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

I. Internment Camp Curriculum and "Performative Citizenship"

While the American education system can serve as a tool to surmount racial oppression, as it did for many African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance, it also has the potential to facilitate injustice. For the Japanese-American students attending school in internment camps during World War II, American education was a dogmatic indoctrination process forced upon a captive audience. The goals and rationale behind internment camp education are revealed in the "Proposed Curriculum Procedures for Japanese Relocation Centers," drafted in 1942 by Stanford University students for the War Relocation Authority. This curriculum outlines ways in which internment camp schools should shape the minds of young internees by upholding democracy as a superlative and quintessentially American concept. Similar to Emily Roxworthy's "myth of performative citizenship," the curriculum is presented as a pathway for children to demonstrate their patriotism in order to build a utopia in which they will no longer be ostracized for their race (Roxworthy 13). However, the hollowness of this promise is uncovered through the document's dehumanizing and stereotypical portrayal of Japanese Americans, highlighting the superficial differences between them and Caucasians while simultaneously reinforcing the internees' status as foreigners. Thus, by presenting American democratic ideology as a defining principle of respected American citizens, the curriculum brands the dominance of American ideals onto the still-forming identities of interned students, asserting that they are not only inferior to Caucasian Americans but also perpetual outsiders, obligated to serve America but never truly be a part of it.

II. The Promise of Peace

A. Education as a Means to End Racism

A poem within the prologue of the curriculum titled: "To the Youth of the Relocation Centers" sheds light on the ways that interned children were motivated by the ultimate goal of world peace and cooperation:

Our plan is but a blue-print which we chose

To mark your way;

You'll "make the desert blossom as the rose;"

You'll mould the clay.

We only hope the means may here be born,

Fragile as they may be,

For folks to work together on that morn

When all the World is free (Armstrong 6).

This poem not only uses imagery such as "You'll mold the clay" to stress children's responsibility to shape society but also presents an idealistic vision of the future defined by freedom for "all the World" and peaceful cooperation (6). The notion of freedom for "all" is significant as it includes people of all races, implying a future of tolerance and interracial harmony. Thus, this poem suggests that if children follow the curriculum, they will help create a world in which they are no longer ostracized for their race. Because the poem's title directly addresses the children, it is likely that this poem was read to interned students. Even if this was not the case, the poem reflects the ideology which internment camp educators were taught to embrace and communicate to their students, and therefore reflects a central concept in the internees' education.

This hollow promise of peace echoes the "myth of performative citizenship," described by Elizabeth Roxworthy as the erroneous assumption that "American citizenship is officially and effectively conferred upon any individual, regardless of race or national origin, based simply upon the performance of a codified repertoire of speech acts and embodied acts" (13). In this context, the "performance" is the act of accepting the values taught in the internment camp with the hope that this loyalty will dissolve racial hierarchies and allow people of Japanese ancestry to become as "American" as their Caucasian counterparts who are not penalized for their heritage. Therefore, this "myth" is particularly powerful in the context of internment camps because of its influence during a period of impressionability and receptiveness prior to adulthood. It resulted in a significant impression on children's identities and an equally severe disillusionment when they discovered that the vision of America that had become intrinsic to their identities was nothing more than a myth.

B. General Education and Embracing Democracy

Having motivated the internees, the curriculum then suggests methods of indoctrination. The primary focus of the internment camp curriculum is "General Education" which is defined as "an effort to give to all children and youth the common understandings of the world in which we live, the attitudes essential to democratic participation in group life, and the skills necessary to satisfactory personal and social existence" (Armstrong 25). This suggests that peaceful coexistence and constructive teamwork is only achievable in a democratic society.

To emphasize the importance of democracy, the camps themselves are presented as microcosms of American government; the description of an internment camp in Chapter I of the curriculum stresses that "both the Japanese-Americans and the Caucasian staff at the Relocation Centers are made acutely aware of the need for working together democratically if life is to be fruitful. Each new arrangement to regulate the affairs of the community becomes subject to examination, and may be rejected or altered if it does not meet the needs of the people" (Armstrong 23), suggesting that the camps themselves are functioning democracies governed by the will of the internees. This reinforces the need for democracy in order for society to function peacefully. Additionally, a table of course topics suggests the theme of "Democracy - An Invention to Satisfy Human Needs" (33) as part of the curriculum for 8th graders, lauding democracy as the key to human satisfaction and modern society. Other examples of forced democratic ideals such as reciting the pledge of allegiance can be found in Ainee Jeong's analysis. Thus, every aspect of the internees' living environment serves as a constant reminder of the importance of democracy.

This strong emphasis on democratic ideals throughout the curriculum stresses the dissimilarities America and Japan by making an implicit contrast between their differing forms of government, contributing to the perception of Japanese culture as "foreign" and separate from America. Furthermore, the assertion that a peaceful society is only attainable through democratic ideals implies that countries with different forms of government, like Japan, are misguided and inferior. By teaching interned children to associate the prominent presence of democracy in their lives with cooperation and harmony, the curriculum also aims to foster loyalty through this idealized portrayal of American culture.

C. Democracy and Identity

Because democracy is presented as a superior form of government, the interned children are likely to absorb democratic ideals as part of their identities. This phenomenon is explained by Karen Coats, who describes children's malleable identities as being shaped "from a range of models, often taking the values of the dominant culture as an important component of their identity structure, even when that culture could be viewed as historically or culturally oppressive" (6). Thus, by constantly emphasizing the dominance of democracy, children are likely to accept it as unquestionable and all-powerful. This, in conjunction with democracy's supposed relation to a promise of peace and post-racial society, suggests that the curriculum aims to produce students who unconsciously accept American government as superior and consequentially imagine Japanese culture as inferior.

III. Unveiling the Myth: Perpetual Foreigners

A. No Promise of Post-War Freedom

The rewards for these acts of performative citizenship are unveiled as a "myth" when a latter section of the proposed curriculum concedes the following uncertainties:

1. The length of the war?

2. Job opportunities after the war?

3. What will happen to the residents after the war:

a. Remain in the centers?

b. Return to original communities?

c. Be distributed to new communities?

d. Return to Japan? (Armstrong 43)

These reservations reveal that not only is citizenship for the internees not guaranteed but even after complying with the curriculum, they may never return to their homes. Moreover, they are still regarded as less-than citizens who can be transported like property and forced to live in the "centers" or "new communities" against their wishes, even after the war ends. Thus, the WRA and authors behind the curriculum never considered the internees as anything but outsiders; the peace that they promised the internees could never be found in the internment camp schools.

B. Emphasis on Dissimilarities

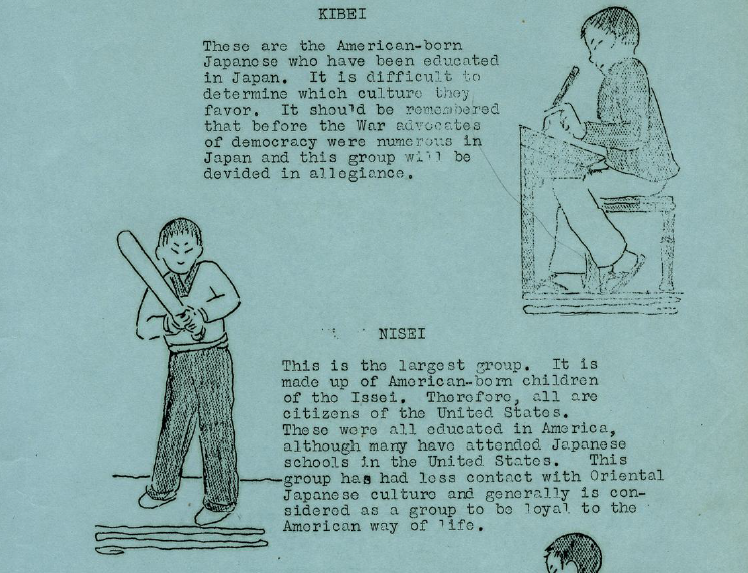

Moreover, the curriculum emphasizes the idea that the internees would never be Americans by highlighting how they are superficially different from Caucasians. For example, in the style of a field guide, Chapter I proposes the following classification of Japanese: "The four main types of Japanese people to be found in the Relocation Centers may be classified according to their nativity and education." The guide then continues to describe Issei, Kibei, Nisei, and Sansei, respectively, complete with illustrations of Japanese children with slanted lines for eyes, dressed in kimonos, studying, and playing baseball (Fig. 2) (Armstrong 10-11). This blatant compliance with stereotypes and "field guide" style not only presents the children as an exotic species but also reinforces the metaphorical distance between Japanese and American culture.

This exoticism is confirmed in a chapter for Caucasian American teachers which describes one's initial feelings upon entering an internment camp: "Except in Japan itself one has seldom seen so many Japanese people at the same time, or all in one place. The strangeness that a member of the Caucasian staff feels the first few times he mingles with the residents of the Relocation Center is shared by many of the Japanese-Americans who were the only people of their race in the towns from which they came" (Armstrong 10). Though the author concedes that both Japanese Americans and Caucasian Americans are alike in their sense of isolation among a different culture, this comparison does not unite them through shared experiences but instead distances the two cultures by reinforcing the idea that the minority group does not "belong" amongst the majority.

IV. The Impact on Japanese American Identity Formation

The result of being consistently regarded as outsiders had a noticeable impact on many Japanese Americans. For example, in an interview in which a previously-interned Nisei requests repatriation to Japan, he explains: "I took in a lot of that stuff about democracy and bettering yourself that they taught me in school" ("A Nisei" 334), after which he describes his optimistic search for employment prior to the realization that "any white foreigner who came here had a better chance than I did. As soon as he learns the language and a few of the local ways he can't be told from anyone else and no one cares where he came from. But I have a Japanese face that I can't change and as long as I live I'll be discriminated against in this country" (335). Thus, his faith in democracy was shattered upon the realization that his beliefs were founded in myth, and that his "Japanese face" distinguished him from Caucasian Americans to such a degree that he would never be accepted. In this case, the impact of this disappointment was severe enough to prompt the man to renounce his American citizenship.

It is clear that by asserting the dominance of American democracy, the internment camp curriculum cultivated loyalty to America while portraying Japanese culture as inferior, giving the internees both a sense of alienation on the basis of race and also a sense of shame for not being on the "dominant" side. While some responded by repatriating to Japan, others chose to abandon their Japanese heritage in a vain attempt to assimilate, as described by Nancy Chung. Thus, by painting any ethnic group as "outsiders," a superficial and temporary level of patriotism is attained; the "foreign" culture will briefly idealize the dominant culture but constantly live in its shadow, ashamed of the inability to "belong." This coerced form of patriotism is nothing but a performance.

Works Cited

Armstrong, Earl, et al. "Proposed Curriculum Procedures for Japanese Relocation Centers." 1942. TS Denshopd-

p171-00189, Helen Amerman Manning Collection. Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Densho Digital Archive.

Web. 3 Nov. 2014.

"A Nisei Requests Repatriation." Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience. Ed.

Lawson Fusao Inada. Berkeley, CA: Heyday, 2000. 333-37. Print.

Coats, Karen. "Identity." Credo Reference. New York University Press, 2011. Web. 16 Nov. 2014.

Fig. 1. Photograph No. 210-G-A78; "San Francisco, California. Flag of allegiance pledge at Raphael Weill Public

School, Geary and Buch . . ., 04/20/1942" Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority,

compiled 1942-1945; Record Group 210: Records of the War Relocation Authority, 1941-1989; National

Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Fig. 2. Armstrong, Earl, et al. "Proposed Curriculum Procedures for Japanese Relocation Centers." 1942. TS

Denshopd-p171-00189, Helen Amerman Manning Collection. Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Densho

Digital Archive. 10. Digital Image.

Roxworthy, Emily. The Spectacle of Japanese American Trauma: Racial Performativity and World War II. Honolulu: U of

Hawaii, 2008. Print.

Additional Resources

Densho Digital Archive

National Archives and Records Administration

Analyses of other Densho Texts

Internment Schools' Impact on the Japanese American Child's Identity Formation at the Individual Level

Identity Formation in Church-Run Schools

“I Remember”: Recalling Childhood

While the American education system can serve as a tool to surmount racial oppression, as it did for many African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance, it also has the potential to facilitate injustice. For the Japanese-American students attending school in internment camps during World War II, American education was a dogmatic indoctrination process forced upon a captive audience. The goals and rationale behind internment camp education are revealed in the "Proposed Curriculum Procedures for Japanese Relocation Centers," drafted in 1942 by Stanford University students for the War Relocation Authority. This curriculum outlines ways in which internment camp schools should shape the minds of young internees by upholding democracy as a superlative and quintessentially American concept. Similar to Emily Roxworthy's "myth of performative citizenship," the curriculum is presented as a pathway for children to demonstrate their patriotism in order to build a utopia in which they will no longer be ostracized for their race (Roxworthy 13). However, the hollowness of this promise is uncovered through the document's dehumanizing and stereotypical portrayal of Japanese Americans, highlighting the superficial differences between them and Caucasians while simultaneously reinforcing the internees' status as foreigners. Thus, by presenting American democratic ideology as a defining principle of respected American citizens, the curriculum brands the dominance of American ideals onto the still-forming identities of interned students, asserting that they are not only inferior to Caucasian Americans but also perpetual outsiders, obligated to serve America but never truly be a part of it.

II. The Promise of Peace

A. Education as a Means to End Racism

A poem within the prologue of the curriculum titled: "To the Youth of the Relocation Centers" sheds light on the ways that interned children were motivated by the ultimate goal of world peace and cooperation:

Our plan is but a blue-print which we chose

To mark your way;

You'll "make the desert blossom as the rose;"

You'll mould the clay.

We only hope the means may here be born,

Fragile as they may be,

For folks to work together on that morn

When all the World is free (Armstrong 6).

This poem not only uses imagery such as "You'll mold the clay" to stress children's responsibility to shape society but also presents an idealistic vision of the future defined by freedom for "all the World" and peaceful cooperation (6). The notion of freedom for "all" is significant as it includes people of all races, implying a future of tolerance and interracial harmony. Thus, this poem suggests that if children follow the curriculum, they will help create a world in which they are no longer ostracized for their race. Because the poem's title directly addresses the children, it is likely that this poem was read to interned students. Even if this was not the case, the poem reflects the ideology which internment camp educators were taught to embrace and communicate to their students, and therefore reflects a central concept in the internees' education.

This hollow promise of peace echoes the "myth of performative citizenship," described by Elizabeth Roxworthy as the erroneous assumption that "American citizenship is officially and effectively conferred upon any individual, regardless of race or national origin, based simply upon the performance of a codified repertoire of speech acts and embodied acts" (13). In this context, the "performance" is the act of accepting the values taught in the internment camp with the hope that this loyalty will dissolve racial hierarchies and allow people of Japanese ancestry to become as "American" as their Caucasian counterparts who are not penalized for their heritage. Therefore, this "myth" is particularly powerful in the context of internment camps because of its influence during a period of impressionability and receptiveness prior to adulthood. It resulted in a significant impression on children's identities and an equally severe disillusionment when they discovered that the vision of America that had become intrinsic to their identities was nothing more than a myth.

B. General Education and Embracing Democracy

Having motivated the internees, the curriculum then suggests methods of indoctrination. The primary focus of the internment camp curriculum is "General Education" which is defined as "an effort to give to all children and youth the common understandings of the world in which we live, the attitudes essential to democratic participation in group life, and the skills necessary to satisfactory personal and social existence" (Armstrong 25). This suggests that peaceful coexistence and constructive teamwork is only achievable in a democratic society.

To emphasize the importance of democracy, the camps themselves are presented as microcosms of American government; the description of an internment camp in Chapter I of the curriculum stresses that "both the Japanese-Americans and the Caucasian staff at the Relocation Centers are made acutely aware of the need for working together democratically if life is to be fruitful. Each new arrangement to regulate the affairs of the community becomes subject to examination, and may be rejected or altered if it does not meet the needs of the people" (Armstrong 23), suggesting that the camps themselves are functioning democracies governed by the will of the internees. This reinforces the need for democracy in order for society to function peacefully. Additionally, a table of course topics suggests the theme of "Democracy - An Invention to Satisfy Human Needs" (33) as part of the curriculum for 8th graders, lauding democracy as the key to human satisfaction and modern society. Other examples of forced democratic ideals such as reciting the pledge of allegiance can be found in Ainee Jeong's analysis. Thus, every aspect of the internees' living environment serves as a constant reminder of the importance of democracy.

This strong emphasis on democratic ideals throughout the curriculum stresses the dissimilarities America and Japan by making an implicit contrast between their differing forms of government, contributing to the perception of Japanese culture as "foreign" and separate from America. Furthermore, the assertion that a peaceful society is only attainable through democratic ideals implies that countries with different forms of government, like Japan, are misguided and inferior. By teaching interned children to associate the prominent presence of democracy in their lives with cooperation and harmony, the curriculum also aims to foster loyalty through this idealized portrayal of American culture.

C. Democracy and Identity

Because democracy is presented as a superior form of government, the interned children are likely to absorb democratic ideals as part of their identities. This phenomenon is explained by Karen Coats, who describes children's malleable identities as being shaped "from a range of models, often taking the values of the dominant culture as an important component of their identity structure, even when that culture could be viewed as historically or culturally oppressive" (6). Thus, by constantly emphasizing the dominance of democracy, children are likely to accept it as unquestionable and all-powerful. This, in conjunction with democracy's supposed relation to a promise of peace and post-racial society, suggests that the curriculum aims to produce students who unconsciously accept American government as superior and consequentially imagine Japanese culture as inferior.

III. Unveiling the Myth: Perpetual Foreigners

A. No Promise of Post-War Freedom

The rewards for these acts of performative citizenship are unveiled as a "myth" when a latter section of the proposed curriculum concedes the following uncertainties:

1. The length of the war?

2. Job opportunities after the war?

3. What will happen to the residents after the war:

a. Remain in the centers?

b. Return to original communities?

c. Be distributed to new communities?

d. Return to Japan? (Armstrong 43)

These reservations reveal that not only is citizenship for the internees not guaranteed but even after complying with the curriculum, they may never return to their homes. Moreover, they are still regarded as less-than citizens who can be transported like property and forced to live in the "centers" or "new communities" against their wishes, even after the war ends. Thus, the WRA and authors behind the curriculum never considered the internees as anything but outsiders; the peace that they promised the internees could never be found in the internment camp schools.

B. Emphasis on Dissimilarities

Moreover, the curriculum emphasizes the idea that the internees would never be Americans by highlighting how they are superficially different from Caucasians. For example, in the style of a field guide, Chapter I proposes the following classification of Japanese: "The four main types of Japanese people to be found in the Relocation Centers may be classified according to their nativity and education." The guide then continues to describe Issei, Kibei, Nisei, and Sansei, respectively, complete with illustrations of Japanese children with slanted lines for eyes, dressed in kimonos, studying, and playing baseball (Fig. 2) (Armstrong 10-11). This blatant compliance with stereotypes and "field guide" style not only presents the children as an exotic species but also reinforces the metaphorical distance between Japanese and American culture.

This exoticism is confirmed in a chapter for Caucasian American teachers which describes one's initial feelings upon entering an internment camp: "Except in Japan itself one has seldom seen so many Japanese people at the same time, or all in one place. The strangeness that a member of the Caucasian staff feels the first few times he mingles with the residents of the Relocation Center is shared by many of the Japanese-Americans who were the only people of their race in the towns from which they came" (Armstrong 10). Though the author concedes that both Japanese Americans and Caucasian Americans are alike in their sense of isolation among a different culture, this comparison does not unite them through shared experiences but instead distances the two cultures by reinforcing the idea that the minority group does not "belong" amongst the majority.

IV. The Impact on Japanese American Identity Formation

The result of being consistently regarded as outsiders had a noticeable impact on many Japanese Americans. For example, in an interview in which a previously-interned Nisei requests repatriation to Japan, he explains: "I took in a lot of that stuff about democracy and bettering yourself that they taught me in school" ("A Nisei" 334), after which he describes his optimistic search for employment prior to the realization that "any white foreigner who came here had a better chance than I did. As soon as he learns the language and a few of the local ways he can't be told from anyone else and no one cares where he came from. But I have a Japanese face that I can't change and as long as I live I'll be discriminated against in this country" (335). Thus, his faith in democracy was shattered upon the realization that his beliefs were founded in myth, and that his "Japanese face" distinguished him from Caucasian Americans to such a degree that he would never be accepted. In this case, the impact of this disappointment was severe enough to prompt the man to renounce his American citizenship.

It is clear that by asserting the dominance of American democracy, the internment camp curriculum cultivated loyalty to America while portraying Japanese culture as inferior, giving the internees both a sense of alienation on the basis of race and also a sense of shame for not being on the "dominant" side. While some responded by repatriating to Japan, others chose to abandon their Japanese heritage in a vain attempt to assimilate, as described by Nancy Chung. Thus, by painting any ethnic group as "outsiders," a superficial and temporary level of patriotism is attained; the "foreign" culture will briefly idealize the dominant culture but constantly live in its shadow, ashamed of the inability to "belong." This coerced form of patriotism is nothing but a performance.

Works Cited

Armstrong, Earl, et al. "Proposed Curriculum Procedures for Japanese Relocation Centers." 1942. TS Denshopd-

p171-00189, Helen Amerman Manning Collection. Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Densho Digital Archive.

Web. 3 Nov. 2014.

"A Nisei Requests Repatriation." Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience. Ed.

Lawson Fusao Inada. Berkeley, CA: Heyday, 2000. 333-37. Print.

Coats, Karen. "Identity." Credo Reference. New York University Press, 2011. Web. 16 Nov. 2014.

Fig. 1. Photograph No. 210-G-A78; "San Francisco, California. Flag of allegiance pledge at Raphael Weill Public

School, Geary and Buch . . ., 04/20/1942" Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority,

compiled 1942-1945; Record Group 210: Records of the War Relocation Authority, 1941-1989; National

Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Fig. 2. Armstrong, Earl, et al. "Proposed Curriculum Procedures for Japanese Relocation Centers." 1942. TS

Denshopd-p171-00189, Helen Amerman Manning Collection. Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Densho

Digital Archive. 10. Digital Image.

Roxworthy, Emily. The Spectacle of Japanese American Trauma: Racial Performativity and World War II. Honolulu: U of

Hawaii, 2008. Print.

Additional Resources

Densho Digital Archive

National Archives and Records Administration

Analyses of other Densho Texts

Internment Schools' Impact on the Japanese American Child's Identity Formation at the Individual Level

Identity Formation in Church-Run Schools

“I Remember”: Recalling Childhood

About the Author |

Kylie Baker |

|

Kylie Baker is pursuing a double major in Spanish and English/Creative Writing at Emory University (17'). She is a fifth-generation Japanese-American interested in the lasting impact of internment camps on Japanese culture and identity. Many of her Japanese-American relatives in California were interned during World War II, while her relatives in Hawaii (including her grandmother) were non-incarcerated but still felt the profound shift in attitudes toward Japanese Americans following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. By curating texts from the Densho Digital Archive, she hopes to show that the impact of internment on the identity of internees still affects the Japanese-American community today.

|